Great Lakes Center Newsletter: Issue 11

October 10, 2017

This issue features a lot of work that is being done locally and across the Great Lakes. Also, there's an exclusive look at the new boat ramp and dock at the Field Station, including plenty of pictures.

GLC completes boat launch, dock improvement project

by Mark Clapsadl

The Field Station has completed a new boat launch and improvements to our dock and shoreline, thanks to funding from the John R. Oishei Foundation, NYS DEC, and the SUNY Construction Fund. Construction took place from July through early September, as a construction crew with excavators, a four-story crane, and many deliveries of concrete limited our access to the water during the field season.

This project addressed several problem areas with the existing boat ramp and the condition of the shoreline and dock. The old boat ramp did not reach far enough or deep enough into the water to launch some of our larger boats during periods of low water so it was replaced with a deeper, longer ramp.

The project was complex, requiring the installation of a cofferdam to permit excavation and framing needed to install a concrete ramp well below water level. The shoreline all along the Black Rock Canal is fill and other debris dating back to the construction of the canal in the 1800’s. This material was quite porous, making installation of a water tight cofferdam a real challenge.

The dock, which is really a 40’ x 60’ steel barge, was capped with concrete and two steel pilings were added to accommodate a 6’ x 30’ floating dock. The floating dock provides a way to moor boats safely even if water levels fluctuate, as can happen during a seiche event. A seiche is a sudden, wind-driven fluctuation in water level fairly common in Lake Erie that can be in the range of 6 feet or more.

In addition, we were able to remove the concrete rubble, steel, old tires, and other assorted debris that constituted the face of the shoreline south of the boat launch and replace it with all with a very stable boulder revetment.

While construction was underway, we had to launch our boats at a ramp offsite on the Niagara River. We were also able to use an old historic ramp that sits at the southernmost part of our property to launch one of our small boats. In the end, the construction was noisy and chaotic, but you can see from the results that it was more than worth it! Look for more pictures in Pictures!.

Building a DNA barcode reference library

by Lyubov Burlakova

The GLC has been awarded $400,000 from the EPA to assemble a DNA Barcode Reference Library for Great Lakes aquatic invertebrates, in collaboration with several US and Canadian universities.

DNA barcoding holds great promise as a way to efficiently detect and identify species by matching sequences from “barcode” genetic regions and comparing the sequences to reference barcodes catalogued in online databases. This process will help future researchers more easily understand the community composition of the benthic fauna. Unfortunately, despite the huge numbers of DNA sequences already deposited in reference databases, these libraries are still incomplete. Although barcode coverage approaches 100% for vertebrates, almost 50% of the zooplankton and benthic invertebrate species known from the Great Lakes lack reference barcodes. Without this information, the ability to implement DNA barcoding as an identification tool for mixed-organism invertebrate samples from the Great Lakes is limited. The development of more complete species-specific libraries of DNA signatures is an essential next step to understand regional biodiversity and to enable more efficient species surveillance programs in the Great Lakes.

We have assembled a large collaborative team that includes experts in barcoding and taxonomy for a wide diversity of aquatic invertebrates. Over the next two years, we will collect and identify specimens of phyla Mollusca, Annelida, Bryozoa, and Cnidaria. The University of Notre Dame and Cornell University (Drs. David Lodge, Lars Rudstam, and James Watkins) will collect and identify specimens of zooplankton and benthic phylum Arthropoda. Barcoding of the samples for this project will be done in Guelph University’s Centre for Biodiversity Genomics under the leadership of Dr. Paul Hebert. Metagenomic analyses of the taxa for this project will be provided by Dr. Michael Pfrender, Director of Genomics & Bioinformatics Core Faculty at the University of Notre Dame.

Some specimens were collected during the R/V Lake Guardian’s summer survey of the Great Lakes. Other mollusc and leech samples have been collected from the shoreline and tributaries of Lake Huron in Michigan, and from Oneida Lake in New York. In the end, we will contribute substantially to the Great Lakes barcode reference library.

Antidepressants found in Niagara River fish

by Kit Hastings

Dr. Alicia Pérez-Fuentetaja has been studying fish in the Niagara River since 2013 with the Emerald Shiner project. The latest news to come out of her research is that human antidepressants are ending up in the brains of fish that live there. The study went viral, being reported locally by the Buffalo News, WHEC Rochester, the Niagara Gazette, and the Duluth News Tribune, but also broadly by the CBC, Forbes, and Politico.

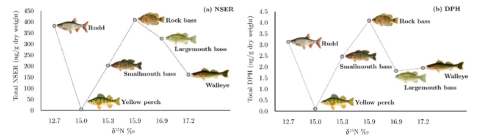

The fish used in the new study, “Selective uptake and bioaccumulation of antidepressants in fish from effluent-impacted Niagara River,” were originally collected in 2015 to analyze the stomach contents of potential predators of the emerald shiner (Notropis atherinoides). Specimens of smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieu), largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), the exotic common rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), rock bass (Ambloplites rupestris), white bass (Morone chrysops), white perch (Morone americana), walleye (Sander vitreus), bowfin (Amia calva), steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), and yellow perch (Perca flavescens) now had their brain, liver, gonad, and muscle tissue analyzed for concentration of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs). Water samples were also taken from locations near where fish were collected in the upper Niagara River, as well as the effluent from two wastewater treatment plants (WWTP), to compare the concentration of PPCPs in the water and in the fish.

The team conducting this study included the GLC, Dr. Diana Aga (UB), Randolph Singh (recent UB graduate), Dr. Prapha Arnnok (Ramkhamhaeng University, Thailand), and Dr. Rodjana Burakham (Khon Kaen University, Thailand). The study found that the major pollutants in the water were the antidepressants citalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, and bupropion, and their metabolites norfluoxetine and norsertraline, as well as the antihistamine diphenhydramine, all of which were found in the fish to differing degrees. The concentrations in the tissues were higher than in water samples, indicating that they had bioaccumulated. Norsertraline and diphenhydramine were found in all species of fish, with the highest levels found in the brain, followed by the liver, muscle, and gonads.

This research is important because it is unusual for bioaccumulation of antidepressants to be reported in wild fish. Studies have shown that antidepressants and their metabolites can influence fish behavior, including predator avoidance, feeding behavior, growth, and reproduction. Also novel was looking at multiple tissues in the same fish. There have not yet been any studies that examine how different antidepressants or PPCPs may work synergistically to alter fish behavior. Levels found in the muscle didn’t appear to be high enough to threaten people who ate the fish.

Pharmaceuticals enter the Niagara River through wastewater treatment plants, which currently have no way to treat water to remove drugs such as antidepressants, antimicrobials, NSAIDS, caffeine, and contraceptive hormones. These drugs all pass through our bodies and aren’t perfectly metabolized, meaning that they and their metabolites end up in the water. Levels of PPCPs are potentially even worse during heavy rain events in the Buffalo area because of combined sewer overflows, which release some untreated sewage mixed with stormwater during weather events.

Possible ways to combat antidepressants in our waterways include pharmaceutical take-back programs and updating WWTPs to treat water for PPCPs. After this study was published, the NYS DEC has announced that they will begin a pharmaceutical take-back program in partnership with pharmacies and retail chains in order to limit the number of drugs being improperly disposed of down the drain. There were already programs to take back pharmaceuticals, but this would expand the program to make it even easier for people to dispose of old medications. Upgrades to WWTPs are still needed to combat increased loads and aging infrastructures, and pharmaceuticals add a new priority to an old problem. A more radical approach to this problem would be for pharmaceutical companies to redesign their drugs so they are more biodegradable, lessening the impact on wildlife.

This isn’t the first time that Dr. Pérez-Fuentetaja has studied the bioaccumulation of chemicals in fish. In 2009, she and Dr. Aga collaborated to look at the bioaccumulation of flame retardants (PBDEs) in fish and other organisms in the Lake Erie food web. Publications from that study were published in 2012 and 2015.

180,000 gobies and counting

by Knut Mehler

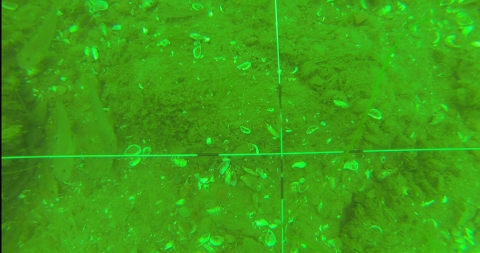

This summer Chris Pennuto and Knut Mehler went out again to the lower Niagara River – joined by a new GLES student, Joe Budnarchuk – to count round gobies (Neogobius melanostomus) using an underwater video camera setup. The round goby is an aggressive invader and has become the most abundant benthic fish in the Niagara River. They not only prey on benthic invertebrates and fish eggs but have also become one of the most important prey items of the lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens).

The objective of this study is to document the seasonal population density and biomass, nutrient content, and nearshore-offshore migration dynamics of round gobies in Lake Ontario and the lower Niagara River. It also addresses the contribution of this fish to off-shore nutrient budget at the ecosystem scale and allows us to estimate the biomass that is available for higher trophic levels.

On average, we found 18 round gobies per m^2 in the lower Niagara River and near-shore areas of Lake Ontario during the summer months, translating into the incredible number of 180,000 fish per hectare. In contrast, almost no round gobies were found during the winter season, suggesting that the fish is migrating to deeper areas in Lake Ontario. Although the overwhelming numbers of round gobies in the lower Niagara River and Lake Ontario can negatively affect the benthic invertebrate community and other fish species, it might also be one of the secrets to why the ancient lake sturgeon is experiencing a comeback.

Gregarious gobies

by Chris Pennuto

Isn’t it always more fun hanging out with your buddies than going it alone? According to an invasive fish, the round goby (Neogobius melanostomus), the answer is maybe. On-going research in the lab of GLC biologist, Dr. Chris Pennuto, is investigating whether that ‘maybe’ is a function of behavioral syndromes in that fish. The basic premise is that the fish constituting an invasion front, or the outer edge of a spatially-expanding population, behave more independently than fish in the core area, which has been colonized the longest. More independent behaviors might include high levels of aggression, greater risk-taking behavior, high exploratory behavior, greater time outside of refugia, or simply avoiding members of the same species (conspecifics).

Dr. Pennuto, along with graduate and undergraduate students in his lab, videotape and analyze the behavior of gobies from core and invasion front areas. They compare such things as swimming frequency and duration and the time spent in the vicinity of conspecifics between fish from the different areas. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of behavior in this fish may lead to better management strategies to slow its expansion into new areas. Dr. Pennuto is looking for a graduate and an undergraduate to join the effort in understanding the role of behavior in invasion biology. Contact him at pennutcm@buffalostate.edu for more info.

A big year for GLES graduations

by Kelly Frothingham

Academic year 2016-2017 was the fourth year that the Great Lakes Ecosystem Science (GLES) M.A. and M.S. programs have been running and it was the biggest year yet for graduations. In May, the GLC celebrated six GLES M.S. students completing their programs, followed by one more M.S. and three GLES M.A. degree conferrals in August. Currently, 80% of the recent graduates are working in the environmental science field. Position titles for some of the 2017 GLES graduates include ecological planner, fish biologist, research support specialist, laboratory technician, and environmental scientist. Graduates are working for agencies including Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Great Lakes Center, and NYS Department of Agriculture and Markets, as well as a local environmental engineering and science consulting firm and a biotech company.

Since the GLES programs started in 2013, a total of 15 students have graduated. 87% of those graduates are working in the environmental science field.

Integrated Pest Management

by Andrea Locke

A key to the long-term success of our efforts at WNY PRISM is integrated pest management (IPM), an ecosystem-based strategy that focuses on using a combination of methods to control invasive species and the harm they cause. Such methods include manual, mechanical, and chemical removal, use of biological controls, habitat restoration, and spread prevention, as well as surveys, monitoring, and continuing assessments. By engaging in IPM when working with our network of partners, WNY PRISM is able to improve the effectiveness of invasive species management efforts in our eight-county region.

Each year WNY PRISM hires a summer crew that works directly with our partners on nearly every aspect of IPM. The Crew splits their time primarily between two IPM related duties: invasive species surveys and invasive species removal.

Invasive species surveys are the first step of IPM, since a management strategy can’t be developed before knowing what threats exist. Armed with a camera, GPS, and iMapInvasives, the Crew works with our partners to map and assess the invasive species present on-site. The crew provides an iMap report and survey summary to our partners at the close of the season, with the expectation that within a couple of years, an invasive species management plan will be developed for each site. WNY PRISM also offers assistance with the development and review of those management plans. In 2017, the crew worked with 5 different partners on 8 individual mapping projects, and entered over 450 observations into iMapInvasives.

Once the surveys are complete and priorities have been established, the process turns towards determining best management practices and developing a plan of action. Manual or mechanical removal may seem like the ideal answer but they may not always be an effective method, depending on the species, age class of the individuals, and the overall level of infestation. Mechanical removal alone may allow for larger areas to be treated with lower cost, but in most cases results only in short-term suppression. These forms of removal may also cause more harm than good. With high levels of infestation, the amount of soil disturbance caused by manual and mechanical removal may negatively impact plant and animal communities far more than the proper application of a selective, non-residual herbicide. In most cases, combining the various methods will provide the most ecologically sound, effective management.

WNY PRISM has been very lucky in that we have had the ability to work with partners on many invasive species removal projects over the years. Some of these projects have even been developed based on past crew surveys. One such project involves knotweed (Reynoutria spp.) removal from Seneca Bluffs. Manual removal had been tried for many years without achieving long-term success. When WNY PRISM became involved, the decision was made to change the management strategy to include a combination of mowing, herbicide, and restoration. Mowing was scheduled approximately 3 weeks ahead of planned herbicide treatments, allowing for the plants to regrow to the ideal management height. This was repeated twice each growing season from 2015 to 2017. Just a few weeks ago, IPM continued with the installation of hundreds of native plants and over 5 lbs. of seed. The removal and restoration aspects of management are often the most rewarding part for our Crew, who not only get to work side by side with our partner and get their hands dirty, but get the opportunity to see the tangible results of many years of planning.

The Crew assisted with many other management efforts this year. Common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) was a frequent target, as the Crew used both cut-stump and hand application treatments to remove the species from Tifft Nature Preserve, College Lodge, Bergen Swamp, and North Tonawanda Audubon Nature Preserve. Water chestnut (Trapa natans) was manually removed by hand from Audubon Community Nature Center in Jamestown, and mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) removal at Kenneglenn Scenic and Nature Preserve in East Aurora was completed using shovels and many volunteers.

WNY PRISM is honored to be a key part of these management efforts, and we look forward to new and exciting projects in the coming years. Learn more at WNY PRISM.

Summer Survey packed to the gills

by Susan Daniel

Scientists from the GLC completed another successful summer survey of all the Great Lakes aboard the 180-foot EPA research vessel Lake Guardian. This is the fifth consecutive year the Great Lakes Center has participated in this science cruise and is the first year within the new grant cycle. Every year, the research vessel leaves Milwaukee, Wisconsin around August 1st and samples Lakes Michigan, Huron, Erie, Ontario, and Superior during a month long survey.

This year’s summer cruise was particularly crowded. Almost 40 people were aboard the Lake Guardian, with about 15 crew members and over 20 scientists, which is close to capacity. That meant that there were three or four people in each cabin and the galley and lounge were often crowded. Researchers from other institutions collected water samples from the rosette for chemical analysis and other special projects.

Scientific crews from the GLC and Cornell University worked together to collect benthic macroinvertebrates, zooplankton, and chlorophyll. Susan Daniel was aboard for the full month; Knut Mehler was there for the first two weeks, and Brian Haas replaced him for the last two weeks. There were seven people from Cornell who rotated throughout the month as well. We collected over 180 benthic samples from 62 stations using a PONAR grab sampler. Sediment samples were also collected this way for grain size analysis and nutrient load. In addition to the usual samples, our researchers collected benthic organisms for the DNA barcoding grant.

We also collected samples to examine the effect of the invasive quagga mussel on surrounding bacterial communities in collaboration with Dr. Vincent Denef (University of Michigan at Ann Arbor). These samples will hopefully help researchers understand how the invasive quagga mussel impacts bacterial abundance, community structure, and functioning.

Benthic samples collected from monitoring stations will be analyzed and the data will be added to the U.S. EPA benthic database, which contains annual data beginning in 1997. These data will shed light on current environmental status of the Great Lakes and provide a baseline for any future changes in water quality. Overall, it was a month of hard work, good food, and calm weather.

Touring Lake Huron

by Kit Hastings

This September, Alexander Karatayev, Knut Mehler, and I spent two weeks sampling Lake Huron for the Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative (CSMI). We joined researchers from the EPA and NOAA and the crew of the R/V Lake Guardian for a detailed look at the organisms that live in the sediment.

Lake Huron is the second largest of the Great Lakes by surface area. There are 30,000 islands, the largest of which is Manitoulin Island, which separates the North Channel from the main basin of the lake. The CSMI survey started in Alpena, Michigan. The first leg of our journey took us through the upper part of Lake Huron and up into the Northern Channel and Georgian Bay. Then we had a few days of shore leave in Alpena before completing sampling in the southern part of Lake Huron. We didn’t sample in Saginaw Bay, another main feature of the lake, because it is too shallow for the Lake Guardian. Instead, Ashley Elgin (NOAA) collected samples there and will send them to us for identification.

At each site, we launched the rosette to collect a profile of the physical and chemical parameters of the water column. Next, we collected three ponars for benthic organisms, one ponar for sediment characterization and sediment nutrient analysis, and sometimes additional ponars to collect mussels for a length-weight analysis by a NOAA researcher. One of the marine technicians also examined surface fluidity of the sediments for an upcoming graduate project. Then, depending on bottom conditions, we towed a benthic sled with a GoPro for 15 minutes to estimate the bottom patchiness and coverage by dreissenid mussels. We collected 298 samples from 100 stations, and took 65 sled tows.

In addition to sample collections, Allison Neubauer, an educator from Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, was aboard the Lake Guardian with us to conduct education outreach. Allison conducted eight video calls with classes of students ranging from 6th grade to college in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin. Their teachers had previously been aboard the Lake Guardian for teacher workshops run by the Center for Great Lakes Literacy (CGLL), a group of Sea Grant educators from around the Great Lakes. While at the workshops, teachers are able to experience what it’s like to collect samples for research firsthand and are given resources to develop curricula to introduce their students to Great Lakes science. Many of these teachers also plan to borrow Hydrolabs from the Limno Loan program to sample the water quality near them. Since the CSMI took place so close to the beginning of the school year, this was their introduction to what they’ll be studying this year. During the video calls, Allison and Beth Hinchey-Malloy (EPA) gave tours of the Lake Guardian, showed various parts of sample collection and processing, and interviewed scientists (including myself) to ask about our research and careers.

In addition to the video calls, classes also participated in a shrinking cup lab. Students measured and decorated Styrofoam cups and sent them to the Lake Guardian, where they were lowered to the bottom of the lake on the rosette. Students on the video calls were able to see their shrunken cups, which will be returned to them to complete the lab. The Shrinking Cup lab was developed by CGLL and is available for different grade levels to explore Boyle’s law. This program is open to teachers who haven’t attended the workshops as well. Typically up to 200 cups are taken each spring and summer survey, and the program is growing.

The weather for the trip was calm, warm, and sunny up until the last day, when the ship encountered some rough seas. We also had some engine and equipment issues, but were able to finish our sampling a little bit ahead of schedule, so it all worked out. We had a wonderful time on Lake Huron, and look forward to next year’s CSMI in Lake Ontario. Look for pictures from our trip in Pictures!.

EPA Great Lakes monitoring grant renewed

by Alexander Karatayev

The GLC has been awarded $2.7 million from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) via sub-contract through a collaboration with Cornell University. The grant, “Great Lakes Long-Term Biological Monitoring Program (LTM): Zooplankton, Benthos, Mysis, and Chlorophyll-a Components for 2017-2022,” continues a monitoring program in the open waters of all five Great Lakes. The LTM is designed to provide managers and scientists across the Great Lakes access to biological data to support environmental decision-making and research. The entire grant of $5.9 million was awarded by the EPA Great Lakes National Program Office (GLNPO) and the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI). Lars Rudstam, Director of the Cornell Biological Field Station, is the principal investigator. The GLC team, led by Lyubov Burlakova and Alexander Karatayev, is responsible for the study of benthic invertebrates.

The LTM project is combined with an assessment of benthos that coincides with the Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative’s (CSMI) 5-year rotation of lakes. While the LTM requires sampling all five lakes at a few selected stations, CSMI studies focus on an intensive survey that includes many more stations in one lake per year.

In addition to the traditional sampling of bottom invertebrates using a Ponar grab, we are applying a novel method to study the distribution and coverage of exotic Dreissena spp. mussels based on the analysis of video obtained from a GoPro camera mounted on a benthic sled towed by the R/V Lake Guardian.

We are also involved in several applied research projects aimed at improving the existing monitoring program and taxonomic expertise, improving our understanding of the linkages between lower trophic levels and fisheries, and informing water quality and fisheries management. These research projects will use data from both the LTM and the CSMI. This work builds on our ongoing involvement with GLNPO since November 2012.

Since the previous grant cycle ended this year, we reapplied to continue participating in the LTM and CSMI for the next five years, as well as adding a DNA barcoding project. In August we were informed that we had officially received the grant. Funding for the project was threatened by proposed budget cuts to EPA this spring. Funding for the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, a vital part of the funding for Great Lakes research, is still being debated as part of a spending bill in Congress.

This is by far the largest grant GLC has received during the last 20 years. It will allow us to continue our cutting edge study of benthic invertebrates across all of the Great Lakes. With it, we will be responsible for the largest benthic monitoring program in the whole Great Lakes region, and one of the largest in the world.

Adjunct research in the Balkans

by Dan Molloy

Last April, Dr. Dan Molloy, an adjunct research scientist with the GLC, took a trip to the Balkans. There, he spent three weeks investigating parasites that are native to the Balkan species Dreissena carinata, a close cousin of invasive zebra and quagga mussels. His research is centered on evaluating parasites of D. carinata as potential biological control agents. His laboratory and field work was conducted in collaboration with scientists from Albania, Macedonia, and Montenegro, respectively, Drs. Spase Shumka (Agricultural University of Tirana), Sasho Trajanovski (Lake Ohrid Hydrobiological Institute), and Vladimir Pesic (University of Montenegro). While in Montenegro, he and his colleagues also collected data on a population of zebra mussels that has been reported to be the first to invade that country. During his stay in the Balkans, he was joined by Drs. Jacque Keele and Yale Passamaneck, molecular biologists from the US Bureau of Reclamation with expertise in genetic identification of dreissenid species and their parasites. Dan Molloy is currently back in the Balkans continuing this study.