![Two people in rain coats pose for a picture amidst a crowd of people. One is holding a sign shaped like a fish that says "I [heart] Great Lakes & Wild River #SaveGLRI"](/sites/glc/files/styles/image_grid_2_xl/public/images/March.jpg?h=7a66d629&itok=FWjBgnqJ)

Great Lakes Center Newsletter: Issue 10

May 8, 2017

The Great Lakes Center is pleased to release the spring issue of our newsletter. This issue features the work of our graduate students, introduces our new research technician, and highlights the March for Science.

Marching for science

by Kit Hastings

![Two people in rain coats pose for a picture amidst a crowd of people. One is holding a sign shaped like a fish that says "I [heart] Great Lakes & Wild River #SaveGLRI"](/sites/glc/files/styles/large/public/images/March.jpg?itok=NL7NeGVF)

On Earth Day, April 22nd, hundreds of thousands of people around the world attended the March for Science to celebrate science, foster accessibility, promote evidence-based policy, and protest proposed cuts to fund research and government agencies involved in protecting the environment. The main march was held in Washington, D.C., and satellite marches and rallies were held in over 600 cities across the U.S. and around the world.

The non-partisan event was organized by scientists and science-enthusiasts, following the success of the Women’s March on January 21st. The March for Science was backed by more than 300 scientific societies, science organizations, and unions for scientists and educators, including United University Professions, a union which represents faculty and staff at Buffalo State.

The March for Science in Washington, D.C., drew tens of thousands of people, including a few members of the GLC. Despite the rain, participants gathered at the Washington Monument for a teach-in and speeches from citizens and scientists, including Bill Nye. Later, the crowd marched to the Capitol.

In Buffalo, an estimated 2,000 people, including some members of the GLC unable to attend the main march, gathered in Delaware Park for a short march and rally.

Early budget proposals slashed funding for the EPA and the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI), major sources for funding for Great Lakes research and restoration projects. A budget deal has passed that preserves most of the EPA's funding through September.

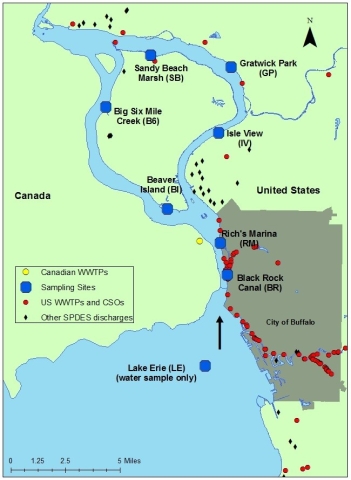

Emerald shiner immune stress in the upper Niagara River

by Jo Johnson, GLES graduate student

For my thesis project I chose to assess the functional health of the Niagara River – whether it can adequately sustain life – by evaluating the health status of a keystone species, the emerald shiner. I hypothesized that sewage input from combined sewer overflows (CSOs) are negatively impacting the immune systems of emerald shiners, which are subjected to this intermittent pollution source.

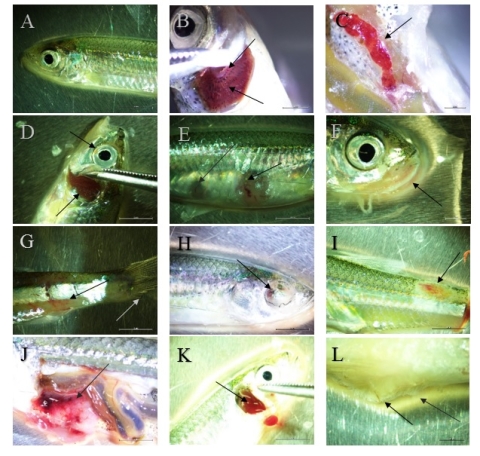

I sampled the Niagara River for emerald shiners at seven sites, biweekly from May to October of 2016. At each site, I also took a water sample for Escherichia coli enumeration, which is a good indicator of fecal contamination sources entering the water. After capturing the fish, I conducted a full necropsy dissection using a method called the Health Assessment Index (HAI). The HAI is a scoring system where a high score indicates that the fish is immunologically stressed and in poor health condition. I then analyzed the health status of the fish population statistically, and made comparisons for fish captured at each site.

The water samples I took showed that the eastern branch of the river (which includes the waterfront from Buffalo and Tonawanda) occasionally had E. coli bacteria levels above EPA regulations and the samples from the Black Rock Canal showed that the water there was consistently degraded. On the western branch of the river, which is the waterfront of Grand Island and Canada and has less sewer input, water coliform samples were within the EPA regulatory levels. Emerald shiners captured from the eastern branch of the Niagara River were in poorer health condition and had a greater number of parasites compared to those captured from the western branch. Additionally, 35% of the emerald shiners captured had bacterial contamination in their livers, which is strong supporting evidence for immune stress in a sewage impacted environment. Some fish exhibited signs of severe systemic stress, such as widespread hemorrhaging, fungal infections, ruptured organs in the internal cavity, and pale, mucous-covered gills. Many of these signs of systemic stress were associated with poor overall condition, high parasite loads, and internal bacterial contamination.

My results showed that emerald shiners captured in the eastern branch of the Niagara, which is highly urbanized and receives a large amount of sewage input, were in poorer health and condition than the fish captured in the western branch. Consistent with other studies, the Niagara River was generally in compliance with legal regulations for E. coli pollution, yet did not appear to be a functionally adequate environment for aquatic organisms living in the river. Most likely there are synergistic effects of all the cumulative pollution and altered water velocities due to hardened shorelines. However, if important forage species such as the emerald shiner are not able to withstand these stressors, there will be irreversible effects on the rest of the food web and the ecosystem. It is imperative that the Niagara River be restored and protected to improve the aquatic habitat, or else we may lose this integral forage fish species, with cascading negative effects to the rest of the food web (sport fish and fishing birds).

Construction

by Kit Hastings

Construction is anticipated this summer at the Field Station. With funding provided from NYS DEC, the Oishei foundation, and the SUNY Capitol Plan, a project has been approved to renovate the boat launch and dock area. The renovation has been in the works for many years but recently all of the funding and paperwork have come together. Construction is expected to begin in July and run through to September, during which time our launch will be unavailable.

Part of the impetus for the project was the extremely low water levels in 2012 that made it difficult or impossible to launch or retrieve our larger boats. The new ramp will be steeper and deeper, thus eliminating the launching problems. Improvements to the existing dock include the addition of floating docks that will provide more secure moorings for our boats during stormy weather.

Scientist visiting from Belarus

by Lyubov Burlakova

Dr. Tamara Makarevich, a professor from Belarusian State University, visited our Center in April. She has been a great colleague and a wonderful friend for over 30 years. Tamara’s primary expertise is in phytoperiphyton (a complex community of algae attached to submerged surfaces in aquatic ecosystem) and she is one of the leading experts in the field. Tamara has been involved in studies of many waterbodies in Belarus but her best known research focuses on the Naroch Lakes (three connected lakes: Naroch, Myasatro, and Batorino).

Naroch Biological Station of the Belarusian State University is the oldest biological station in Belarus and one of the oldest in the Former Soviet Union. Operating since the late 1940s, it became famous for profound research on ecosystem functioning processes and biological productivity, as well as the long-term monitoring of the lakes. In the late 1980s to early 1990s, these lakes were colonized by exotic zebra mussels which caused dramatic changes in their ecosystems. At almost exactly the same time, zebra mussels colonized the Laurentian Great Lakes and many other lakes in North America, including Oneida Lake in New York. Oneida Lake has been studied for many years by researchers from the Cornell Biological Field Station.

The presence of a long-term extensive dataset on the aquatic chemistry and biological communities of all these lakes before and after the zebra mussel invasion creates a unique opportunity to reveal dramatic ecosystem changes caused by the invader in the Old and New World. Tamara’s visit is the first event in a long-term collaboration between Belarusian and North American scientists. The main goal is to reveal the mechanisms and consequences of freshwater ecosystem responses to the invasion of exotic molluscs in Europe and North America. Two more scientists from Belarus, Drs. Boris Adamovich and Hanna Zhukava are planning to visit GLC and Cornell Biological Station in July.

In addition to the analysis on database with Narochanskie lakes, Tamara also presented her research to the faculty and students of the Great Lakes Center.

GLES program seeks graduate students

The GLES M.A. Program is recruiting new graduate assistants (GA) to begin thesis programs in Fall 2018. Initial GA appointment would be for the 2017-2018 academic year, renewable for a second year if the student is making satisfactory academic progress. The GA includes an in-state tuition scholarship (up to 9 credits per semester) and a $7,500 stipend.

Some additional information about the GLES GA:

- Must be a full time GLES M.A. student and carry an approved academic load.

- GAs assist faculty in their teaching or research responsibilities. The work performed by a GA requires an average of 20 hours per week. Students should have research and/or teaching responsibilities beyond their thesis research project. Responsibilities may include, but are not limited to, research assistant duties (e.g., performing field or lab work on non-thesis research projects) or teaching assistant duties (e.g., tutoring, holding office hours, grading).

- Reappointment is contingent on a student’s effectiveness as a GA, their performance in course work, and progress on their degree.

Interested students are encourage to contact a potential thesis faculty advisor to determine if faculty are accepting new students into their lab. Considerations will begin on May 1, 2017.

Mudpuppies

by Dr. Chris Pennuto and Adam Haines, Biology graduate student

At the bottom of many lakes, rivers and streams in New York lies a largely misunderstood, understudied, and very fascinating animal. This animal’s scientific name is Necturus maculosus, better known as the common mudpuppy. Mudpuppies, although sounding like a cute little canine in need of a bath, are a large, purely aquatic species of salamander. These salamanders have the largest distribution of any purely aquatic species of salamander in North America, ranging from Louisiana, east to Georgia and north into southern Canada, encompassing the Great Lakes region and most of New York. Mudpuppies can grow to over 19 inches long and live to be over 35 years old! Whereas many salamander species have external gills when immature and absorb them when they become mature terrestrial adults, mudpuppies retain their external gills and remain in water their whole lives. They prefer habitats that have plenty of cover for them to hide under and to use as nests when it is time to reproduce. Despite being a cold-blooded animal, mudpuppies prefer colder water temperature and typically are only seen during fall, winter and early spring months, when they are most active. Ice fishermen occasionally catch them while fishing, and sometimes they are discarded on the ice to die due to the belief that they are poisonous, which they are not. This lack of knowledge is not exclusive to fishermen; not much is known about mudpuppy life history plasticity and distribution throughout much of its range, especially in New York.

Adam Haines, a biology graduate student, is addressing some of the knowledge gaps in mudpuppy distribution and life history plasticity as part of his thesis research. The first part of his study is a presence/absence survey of mudpuppies for the eight western New York counties (Allegany, Cattaraugus, Chautauqua, Erie, Monroe, Niagara, Genesee, and Wyoming). This part of his thesis will update the HerpAtlas compiled by NYSDEC. He has already documented the occurrence of mudpuppies in an Erie County stream which previously had no record of them!

The second part of his thesis will describe differences between populations of mudpuppies in lentic (lake) and lotic (stream) environments. Since lake and stream habitats differ in their depth profiles, temperature variability, hydrodynamics, prey base, and many other ways, it is likely that mudpuppy behavior, physiology, or morphology may also differ to best survive in either habitat type. For example, literature suggests lake populations migrate offshore in the summer as water temperatures rise nearshore. However, mudpuppies in lotic environments do not have this luxury because, well, streams don’t get that deep. Adam is asking whether this behavior might be shaped by the type of habitat a mudpuppy resides in. This habitat-induced difference in behavior is called phenotypic plasticity. Phenotypic plasticity is defined as morphological, physiological, or behavioral traits exhibited by a genotype that differ in different environmental conditions. Similarly, body morphology may be different between the habitats as mudpuppies wrestle with hydrodynamic differences. Body measurements such as total length-to-girth ratios, head width, or tail depth are expected to be different between the two different environments.

Any students who would like to become involved in this study, please contact Adam Haines (hainesam01@mail.buffalostate.edu) or stop by Dr. Pennuto’s lab (327 SAMC). Field work includes falling into streams, handling smelly catfood, swimming in cold water for lost traps and breaking through ice with various items, as well as PIT-tagging, swabbing for chytrid fungus, and handling these amazing animals.

Congratulations on your graduation, Susie!

by Lyuba Burlakova and Sasha Karatayev

Susie Daniel is graduating this semester with a Master of Science degree in Great Lakes Ecosystem Science! We are very happy for you, Susie!

We first met Susie in 2011 at the 54th Annual Conference of the International Association for Great Lakes Research (IAGLR) in Duluth. At that time, Susie was an undergraduate student at Heidelberg University. She attended our session, introduced herself, and had many questions for almost every speaker.

In 2012, we received funding from the U.S. EPA for the long-term biological monitoring of the lower food webs of the Great Lakes, and started our search for a qualified candidate to do taxonomic identification of benthos. This was not a simple task, as taxonomy is now called a dying field mostly due to the long training period needed to become an expert. However, we were very fortunate because our colleague Dr. Kenneth Krieger, Director of the National Center for Water Quality Research (NCWQR) at Heidelberg University, is the leading taxonomic expert in benthos of the Great Lakes Region. Susie was employed as a technician at NCWQR as an undergraduate and Ken trained her in species preparation and identification. Ken characterized Susie as “an outstanding student.” We hired Susie in May 2013, a few days after she graduated, and what an excellent choice we made!

Susie is a very hard working and dedicated researcher, a quick and keen learner, and constantly improving her skills. Susie is an excellent lab manager and coordinator, handling all the procedures of sampling processing for the project, from collection to record entry, and she does everything very well. She is also a great tutor, having already trained many students and technicians in sorting and identification. We believe that her upbringing in a wonderful family with a very high work ethic laid a great foundation for her success and future career. Susie is very enthusiastic and has been passionate about science since and early age, and she’s always eager to learn.

In 2013, we started working together on a project to study the effect of exotic Dreissena on benthic community, and in 2014, she enrolled in the GLES program. Since 2014, Susie has presented her research annually at IAGLR. In 2015, her presentation, “Effect of Dreissena on Profundal Oligochaeta Community,” won the Poster Award for Information Impact. In 2015, she was nominated as a U.S. Student Member to the IAGLR Board of Directors, and since 2016 she has served this great international organization that promotes scientific understanding and collaboration.

Years of work, classes, and exams are over. Susie, enjoy your graduation ceremony, and we are looking forward to many years of exciting research together!!

Lyuba Burlakova

Sasha Karatayev

Our new research technician

by Kit Hastings

This spring, the GLC hired Brian Haas to be our new research technician at the Field Station. Brian will spend much of his time doing fieldwork and maintaining the boats, but will also spend some time in the lab. Brian started working in the last week of April and has already helped out with launching the GLOS buoy and with teaching a fisheries class.

Prior to this appointment, Brian worked for two and a half years on the Upper Niagara River conducting a biotelemetric study of northern map turtles (Graptemys geographica) for his Master’s thesis with Dr. Ed Standora in the Biology department. His research focused on habitat use, behavior, and movement of tagged turtles.

After graduating from SUNY Buffalo State in 2015, he took a job at an environmental consulting firm where he conducted wetland delineations, invasive species surveys, and endangered species assessments. He worked there as an environmental scientist, until he took the opportunity to return to his Alma Mater.

Brian's experience with boats and research make him a great fit for the Field Station. We're glad to have you on board, Brian!